Radio documentary is a factual, informative audio program that is broadcast over the air by radio stations or streamed on the internet. Radio documentaries can include recorded interviews, debates, and statistics to be shared with listeners. Both historical events and current issues can be discussed.

What Is Documentary And Its Types As with radio dramas, radio documentaries rely on audio techniques to engage the audience, allowing listeners to visualize what is being described. Tone of voice, use of background music, and choice of sound effects are all very important in developing a quality radio documentary. Documentary filmmaking is a powerful and vital element to our society, and those who are responsible for bringing real stories and issues to a creative medium often have an uncanny ability to make a deep connection to us with their art. Legendary directors and cinematographers such as the Maysles brothers, D.A. Pennabaker & Chris Hegedus, Errol Morris, or Ken Burns have vividly made their marks in recent decades and continue to inspire those who enter the field.

Inexpensive video camera equipment and video editing software have helped fuel a new wave of truth-tellers, bringing the tools of the craft within reach of amateurs and students, as well as independent journalists and filmmakers on a budget. Stories and pieces that explore how recorded sound has captured history, how sound recording has changed the course of history, and how the sound of life has changed over the past century. An ambitious project of short segments and long-format programs that will be aired on some of NPRs most popular programs, its producers will also be asking public radio listeners to search for and share their own families audio histories . Third, the form of a film is the formative process, including the filmmakers' original conception, the sights and sounds selected for use, and the structures into which they are fitted. Documentaries, whether scripted in advance or confined to recorded spontaneous action, are derived from and limited to actuality. Documentary filmmakers confine themselves to extracting and arranging from what already exists rather than making up content.

They may recreate what they have observed but they do not create totally out of' imagination as creators of stories can do. Though documentarians may follow a chronological line and include people in their films, they do not employ plot or character development as standard means of organization as do fiction filmmakers. The form of a documentary is mainly determined by subject, purpose, and approach. Usually there is no conventional dramaturgical progression from exposition to complication to discovery to climax to denouement. Documentary forms tend to be functional, varied and looser than those of short stories, novels, or plays.

They are more like non-narrative literary forms, such as essays, advertisements, editorials, or poems. Documentary is one of three basic creative modes in film, the other two being narrative fiction and experimental avant-garde. Narrative fiction we know as the feature-length entertainment films we see in theaters on a Friday night or on our TV screens; they grow out of literary and theatrical traditions. Experimental or avant-garde films are usually shorts, shown in nontheatrical film societies or series on campuses and in museums; usually they are the work of individual filmmakers and grow out of the tradition of the visual arts. One approach to the theory, technique, and history of the documentary film might be to describe what the films generally called documentaries have in common, and the ways in which they differ from other types of film.

Another possible approach would be to consider how documentary filmmakers define the kinds of films they make. The second aspect--purpose/point of view/approach--is what the filmmakers are trying to say about the subjects of their film. They record social and cultural phenomena they consider significant in order to inform us about these people, events, places, institutions, and problems. In so doing, documentary filmmakers intend to increase our understanding of, our interest in, and perhaps our sympathy for their subjects.

They may hope that through this means of informal education they will enable us to live our lives a little more fully and intelligently. At any rate, the purpose or approach of the makers of most documentary films is to record and interpret the actuality in front of' the camera and microphone in order to inform and/or persuade us to hold some attitude or take some action in relation to their subjects. Trained as an historian I labored throughout the 1980s as an independent documentary producer and historical consultant.

Much of my work was in public radio, for which I produced two oral history-based documentary series and served as the first producer of Crossroads, a national weekly radio magazine on multi-cultural affairs. The documentary, a genre as old as cinema itself, has traditionally aspired to objectivity. Whether making ethnographic, propagandistic, or educational films, documentarians have pointed the camera outward, drawing as little attention to themselves as possible. In recent decades, however, a new kind of documentary has emerged in which the filmmaker has become the subject of the work. Whether chronicling family history, sexual identity, or a personal or social world, this new generation of nonfiction filmmakers has defiantly embraced autobiography. In The Subject of Documentary, Michael Renov focuses on how documentary filmmaking has become an important means for both examining and constructing selfhood.

Pioneering participatory, social change-oriented media, the program had a national and international impact on documentary film-making, yet this is the first comprehensive history and analysis of its work. The volume's contributors study dozens of films produced by the program, their themes, aesthetics, and politics, and evaluate their legacy and the program's place in Canadian, Québécois, and world cinema. An informative and nuanced look at a cinematic movement, Challenge for Change reemphasizes not just the importance of the NFB and its programs but also the role documentaries can play in improving the world. Radio documentary is a spoken word radio format devoted to non-fiction narrative.

It is broadcast on radio as well as distributed through media such as tape, CD, and podcast. A radio documentary, or feature, covers a topic in depth from one or more perspectives, often featuring interviews, commentary, and sound pictures. A radio feature may include original music compositions and creative sound design or can resemble traditional journalistic radio reporting, but covering an issue in greater depth. I think there has always been great creativity in the radio industry and you can listen to an old documentary and be just as hooked today as when it was first broadcast.

Because at its heart, it's all about really good storytelling. Perhaps people can now be more experimental with structure - not necessarily telling a story in a linear way. But I think a major influence on many producers has been "Serial", and some other American podcasts that have let the audience in on the process of making the piece.

It's a nice way to be more intimate with the audience, and more honest about what has and hasn't worked, but we have to be careful it doesn't become a cliche. I wonder whether the next steps might involve the audience even more, in terms of collaboration - it's so much easier to make good quality recordings, even on smart phones, that more and more listeners can become citizen journalists. A radio documentary is a documentary programme devoted to covering a particular topic in some depth, usually with a mixture of commentary and sound pictures. Radio Feature often is used as a synonym of radio documentary. Though radio feature resembles a documentary in the way it is made, but differs in its larger scope and subject/time variability. Radio magazine is an umbrella programme on a particular subject, which can have several programmes in it- documentary, features, interviews, music etc.

The expanding national system of public and community radio stations created the outlets for documentaries produced by both station-based and independent producers, a number of whom were drawn quite naturally to the use of oral histories. Almada, who has made several films about Mexican history and life in the U.S./Mexico border region, raises issues about documentary film as an art form as well as the responsibility of a filmmaker to be sensitive to her subjects. She also discusses sound editing and what choices best represent the events she documented. Among the various definitions of documentary, one offered by Raymond Spottiswoode in A Grammar of the Film, first published in 1935, seems to me among the most adequate; certainly it applies quite satisfactorily to documentaries of the 1930s. Spottiswoode does not acknowledge as part of documentary the filmmakers' social purposes or their concern with the effects of their films on audiences.

He was subsequently hired by Grierson at the General Post Office Film Unit as a "tea boy"--a general assistant, what we could call a gopher ("go for" this and that). According to a popular anecdote, when Grierson read A Grammar of the Film he decided that Spottiswoode had better remain in that humble position a while longer. Grierson regarded the purposes and effects of films of ultimate importance. As for subjects--what they're about--documentaries focus on something other than the general human condition involving individual human actions and relationships, the province of narrative fiction and drama. City of Gold , made at the National Film Board of' Canada by Wolf Koenig and Colin Low, comprises still photographs taken in Dawson City in 1898 set within a live-action frame of the actualities of present-day Dawson City.

In terms of' library catalogue headings, City of Gold would be listed under "Canada. History. Nineteenth century," "Gold mines and mining. Yukon," "Klondike gold fields," and the like. Generally, documentaries are about something specific and factual and concern public matters rather than private ones. The people, places, and events in them are actual and usually contemporary. "Germany, Denmark and Sweden all have very sound-rich traditions that emanate from the 1960s and '70s," says Steven Rajam, an English audio-maker who resides in Wales. There is also an abundance of European audio documentary that is made in languages other than English.

"Radio Atlas, run by Eleanor McDowall, is an absolute treasure trove of European documentary," says Rajam. This is a way to get access to international stories that are different from what an English-speaking audience would get access to. Plus, audio is not dubbed, so the audience hears the original voices and sound design without the "distraction" of a voice dubbed in English over the original.

Documentarians often record copyrighted sounds and images when they are filming sequences in real-life settings. Common examples are the text of a poster on a wall, music playing on a radio, and television programming heard in the background. In the context of the documentary, the incidentally captured material is an integral part of the ordinary reality being documented. Only by altering and thus falsifying the reality they film— such as telling subjects to turn off the radio, take down a poster, or turn off the TV—could documentarians avoid this. People use their voices and listen to others' voices each and every day.

As Dolar suggests, "all of our social life is mediated by the voice."38 Whenever people are in environments that are full of sounds, human voices are usually the first ones that capture their attention. The strength of Lot 63, Grave C comes not from the choice of plot or the story, but from the way Green presents it. Apart from a few newspaper articles on microfilm and the stabbing footage, Green had no visual material on Hunter.10 Although this is a major problem when producing a documentary, Green overcame this by using a narration style different from those in conventional documentaries.

He follows Edward Wilkes, the general manager of Skyview Memorial Lawn, the cemetery where Hunter's grave is located, and tells about Hunter through Wilkes's words. Instead of interviewing Wilkes in front of the camera, Green constructs his way of storytelling by following Wilkes as he walks from the entrance gate of the cemetery to Hunter's grave. During this walk, Green uses Wilkes's voice mostly off-screen, but in some instances he also shows Wilkes talking.

The film is almost ten minutes in length, and nearly five minutes of it include shots of Wilkes walking and standing, and other cemetery scenes on Wilkes's way from the gate to Hunter's grave. Green also uses intertitles to give brief information about the Altamont Speedway Free Concert and the incident that happened that day. The film includes footage of Hunter's stabbing from Gimme Shelter and shots of newspaper clippings on microfilm.

Finding the theoretical space where cinema and philosophy meet, Malin Wahlberg's sophisticated approach to the experience of documentary film aligns with attempts to reconsider the premises of existential phenomenology. The configuration of time is crucial in organizing the sensory affects of film in general but, as Wahlberg adroitly demonstrates, in nonfiction films the problem of managing time is writ large by the moving image's interaction with social memory and historical figures. The formula that emerged by the late 1940s is structured by a linear storyline that impels the story forward and a sonically elementary production style that makes more sense visually than auditorally.

The whole formula is premised upon the assumption that the listener must be able to get all there is to hear in a single listening. What is important from the perspective of the history of the audio documentary is that NPR and the public radio system was drying up as a market for independently produced, radio documentary series. Inspired by British and Canadian programming, radio documentary producers in the United States survived at small, volunteer-staffed educational radio stations, the preponderance of which were based at the old land-grant colleges and state universities of the Midwest.

The human voice is so significant that in music production, it is usually the singer's voice that is the main focus. The film in which the filmmaker is the most prominent is Headbanger's Journey. It follows Dunn, he is on camera, the story is narrated by him, he interviews the subjects himself, and he is heavily involved with them. Compared to Dunn, Spheeris's presence in The Decline of Western Civilization and especially Bendjelloul's presence in Searching for Sugar Man are much less prominent. Nevertheless, the directors' involvements with their subjects and their actions place these three films in participatory mode. In Lot 63, Grave C, Green appears on camera momentarily, holding a microphone to interview Wilkes.

Even his brief presence is enough to keep the film in the field of documentary. Crossing the Bridge, on the other hand, with the total absence of the filmmaker, and with its style that narrates the film through Hacke, a subject—almost a fictional character—blurs the boundaries between documentary and fiction. Hacke interacts with the subjects and he even plays songs with some of them. Searching for Sugar Man is a documentary about the search for mysterious American singer and songwriter Sixto Rodriguez. The Detroit-based folk musician had two albums released in the United States; neither of them sold well, so the record company dropped him. Then in the early 1970s, unbeknownst to Rodriguez, his albums somehow reached Cape Town, South Africa, where through the hand-to-hand exchange of bootleg copies his songs became an anti-establishment inspiration.

Rodriguez, although an unseen figure, turned into a star comparable to Bob Dylan or the Beatles. In the 1990s two South African fans, Stephen "Sugar" Segerman and Craig Bartholomew Strydom, set out on a search for Rodriguez to find out who he really was and what happened to him. Although Searching for Sugar Man tells the story of the search for Rodriguez by Segerman and Strydom, and even though the plot of the film and the backbone information are conveyed by them, the film does not follow them. As a matter of fact, the film does not follow any person—not even Rodriguez himself, who appears on camera in the second half of the film. Bendjelloul builds a narrative structure on interviews, not only with Segerman, Strydom, and Rodriguez, but also with other people connected to Rodriguez, and he supports the interviews with new and archival footage and animations. Good audio documentary producers live all over the country and can be located through one's local public radio station, NPR, or through the Association of Independents in Radio , the national association of independent radio producers.

Relying heavily on pieces supplied by member stations and independent producers, NPR's programming may have suffered from uneven quality, but was varied and exciting, and at times riveting. Unrestricted by the old radio documentary and news report formulas, young producers such as Joe Frank, Josh Darsa, and Robert Montiegal extended the ATC emphasis on sound. Poetic documentaries, which first appeared in the 1920's, were a sort of reaction against both the content and the rapidly crystallizing grammar of the early fiction film. The poetic mode moved away from continuity editing and instead organized images of the material world by means of associations and patterns, both in terms of time and space.

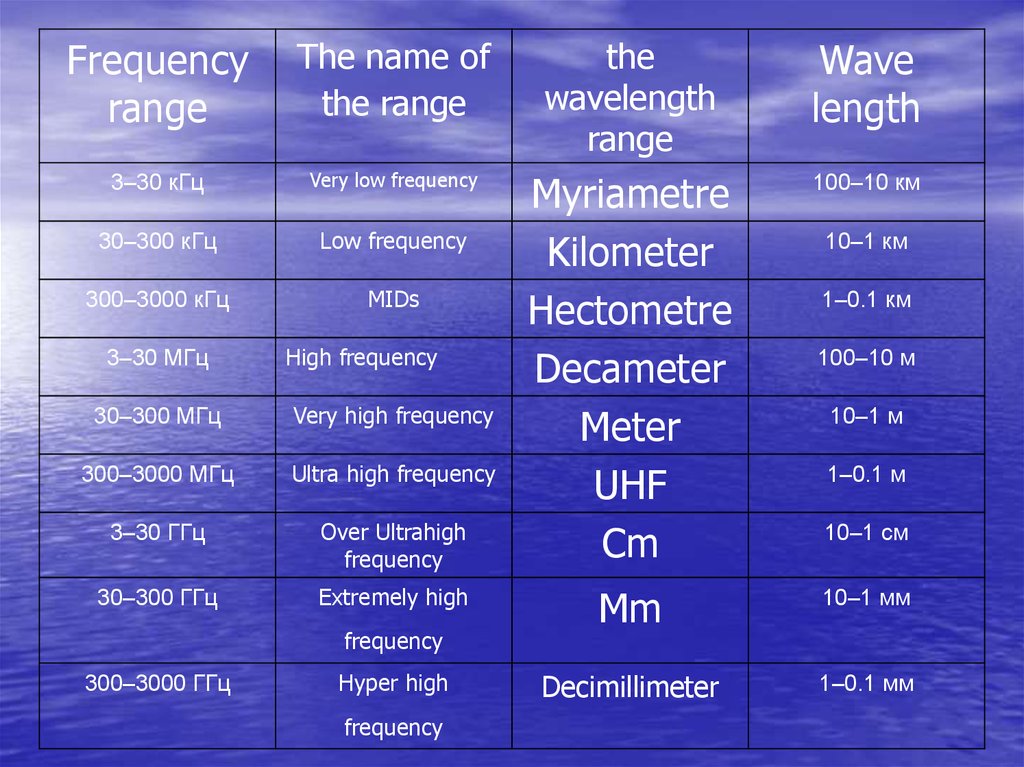

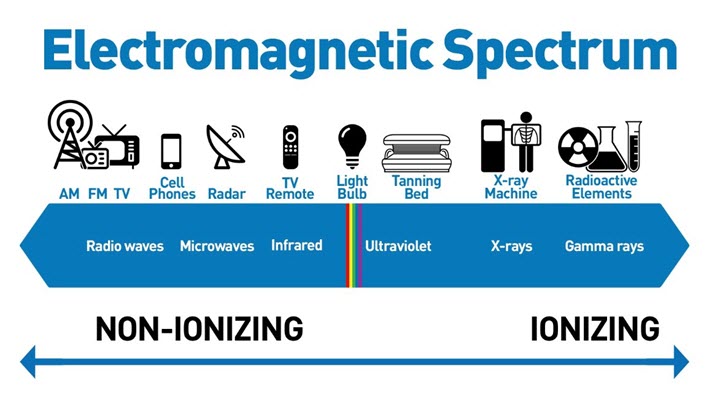

Well-rounded characters—'life-like people'—were absent; instead, people appeared in these films as entities, just like any other, that are found in the material world. Their disruption of the coherence of time and space—a coherence favored by the fiction films of the day—can also be seen as an element of the modernist counter-model of cinematic narrative. The 'real world'—Nichols calls it the "historical world"—was broken up into fragments and aesthetically reconstituted using film form. There have been spectacular technological advances in Radio, both in production and delivery platform. Digital technology has almost replaced analogue, leading to ease of production and to convergence on a wider scale and platform.

There could be multimedia content- with bits of audio, print and visuals strung together. One has to be aware of the advances in order to take advantages of the features for better reach, access and listening pleasure of the audience. In another of its forms, documentary research couples dissonant paradigms of managing and ascertaining documentary evidence, as conceived in the traditional social sciences, with creating and formulating aesthetic presentations, as conceived from the arts and humanities. The aesthetics of documentary studies brings attention to the modes of narration and the protocols of subjectivities (Austin & de Jong, 2008).

By now, students should begin to identify a few things that distinguish a documentary from a news report. They may notice that both forms use interviews, but the length of those interviews tends to be longer in a documentary. Or they may notice that news reporters try to separate themselves personally from their subjects, while documentarians often share personal stories and are interested in conveying particular perspectives rather than making sure that all possible voices are heard.

They may notice that documentaries use film as an art form or use humor in ways that news does not. Instead of filmmaking methods, other documentarians have centered their definitions around the purposes, functions, and effects of documentary. Indeed, Rotha did not exclude the use of actors and studios from documentary as long as the filmmaker's purpose was to help a society function better, to contribute to more satisfying lives for its people. Documentary has as its root word document, which comes from the Latin docere, to teach.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.